- Subscribe

Get full access to Maritime Journal content

Including the digital magazine, full news archive, podcasts, webinars and articles on innovations and current trends in the commercial marine industry.

- Expert analysis and comment

- Unlimited access to in-depth articles and premium content

- Full access to all our online archive

Alternatively REGISTER for website access and sign up for email alerts

- Special Reports

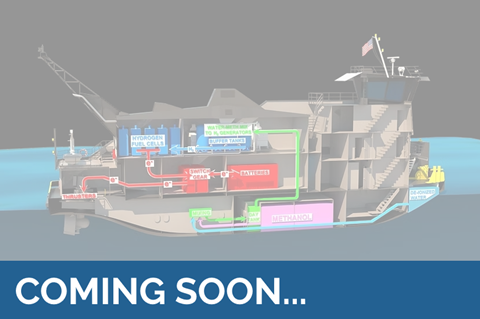

Batteries in Maritime

Autonomy at Sea

Alternative Fuels

Tugs, Towing & Salvage

Examining the growing role of batteries in maritime, questioning their green credentials while exploring industry insights, operator experiences and lessons learned from early electric vessel adoption worldwide. Highlighting the innovators advancing subsea and maritime technology, from autonomous underwater swarms to cloud-connected assets and data-driven predictive models, reshaping how real-time conditions at sea are understood globally today. Exploring one of the workboat sector’s dilemmas today: which emerging fuels hold the most promise in terms of cost, availability, practicality and performance? Or should we simply clean up the Black Gold? Looking at how tugs, towing and salvage vessels are adapting to stricter regulations; contemplating new propulsion technologies and alternative fuels; and changing design strategies for one of maritime’s most demanding sectors. Read More Read More Read More Read More

- Industry Database

- Events

Seawork

9th - 11th June 2026Speed@Seawork

8th June 2026Seawork Conferences

The 27th edition of Europe’s largest commercial marine and workboat exhibition provides businesses the opportunity to showcase their services, equipment, vessels and supplies to an international audience. Speed@Seawork on 8th June in Cowes offers a sector specific event that showcases fast vessels operating at high speed for security interventions and Search & Rescue. "Get Set for Workboat 2050", in partnership with Seawork, Maritime Journal and The Workboat Association, is a series of conferences which deal with decarbonisation and all aspects of improving OPEX efficiencies. Visit the Seawork Website Speed@Seawork on the Seawork Website View on Seawork

Offshore Wind in Poland - Riding the Winds of Opportunity?

2016-04-15T17:03:00

Poland is gradually emerging as a potentially important investment market for offshore wind - but although a number of international companies continue to show an interest in investing in the country''s onshore sector, progress in offshore development remains sluggish.

This is premium content

Already a member? SIGN IN now

Register for a FREE one-month trial to continue this article

It only takes a minute to sign up for a free account, and you’ll get to enjoy:

- Weekly newsletters providing valuable news and information on the commercial marine sector

- Access to the Maritime Journal Industry Database

- Website access (3 standard news articles per month)

Get access and more free content sign up today

Does your organisation require more access? Upgrade to a subscription and enjoy unlimited news and additional features.

- Terms & Conditions

- Cookie Policy

- Privacy Policy

- © 2024 Maritime Journal

Site powered by Webvision Cloud